Sometimes the comic books you saw in ads but didn’t read could be as fascinating as the comics that you'd paid your dime or 12 cents to buy. They might even be more compelling, because not knowing the story behind the covers forced you into the delightful practice of using your imagination and speculating — of writing, in effect, just the way Stan Lee, Gardner Fox and John Broome did. So welcome to Just Imagine: The Colorful World of Comic Book House Ads.

June 1938: A Superman for the Underdog

On the newsstands in May 1938, browsers had their choice of Tarzan in Comics on Parade, Popeye in King Comics, daredevil aviator Captai...

-

In Tales of Suspense 49 (Jan. 1964), Iron Man would use his new armor to withstand a nuclear detonation and rescue a member of the X-Me...

-

For the 10-and-under crowd, Showcase 34 contained not only the debut of a new superhero, but a thrilling surprise. A text feature gave us ...

-

By the time the X-Men debuted in September 1963, we Marvel fans already prided ourselves on insider knowledge. The Beast we recognized as a ...

Wednesday, March 4, 2020

Monday, July 8, 2013

October 1983: A Champion by Chance

A kind of latter-day Fly Girl, AC Comics’ heroine Nancy Arazello was appealing and unassuming, feeling her way toward independence both as a woman and as a superhero.

She only became a superhero, in fact, because she’d accidentally interrupted her boyfriend when he was beseeching the dark insect god Zzara for power.

“During the 1940s, student of the occult John Howard Gallagher performed a mystic ritual which gave him super powers,” noted Jeff Rovin in his Encyclopedia of Superheroes. “Engineer Kenneth Francis Burton Jr. spends years learning all he can about Gallagher, who had died in 1957 — and eventually learns the secret of the incantation. But while he was performing the ceremony at his factory, his fiancée Nancy walks in and receives the full force of the unleashed supernatural powers. Thereafter, simply by willing it, she becomes the Dragonfly, able to fly and possessing great strength and invulnerability.”

In fact, she could reach speeds of Mach 4 and move objects with telekinesis. She came with a built-in enemy, a boyfriend who seethed with envy over the powers he thought were rightfully his.

As T.M. Maple observed, “(Writer/artist) Rik Levins did seem to have a good time with the story, interjecting some of the more mundane, nevertheless interesting and amusing, problems that a superhero might run into.”

The character could be seen as a more mature homage to Fly Girl, with the 1950s’ male superhero who preceded her analogous to the Fly, and perhaps Charlton’s mystically powered Blue Beetle.

Nancy also had something in common with the Greatest American Hero as a goodhearted, accidentally super-powered person who was somewhat out of her depth.

Introduced in Americomics 4 (Oct. 1983), Dragonfly went on to star in eight issues of her own title.

I’ve always thought Dragonfly was among those well-done “might-have-beens,” a character who had some of the freshness Spider-Man originally possessed, and who deserved better than she got.

Saturday, April 6, 2013

June 1977: The Long Reach of the Unseen Hand

The inventive British novelist H.G. Wells contributed several conventions that have become mainstays in superhero comics — among them time travel, interplanetary warfare and, oh joy of joys, invisibility.

The concept of human invisibility is a wish fulfillment fantasy that probably predates recorded history. We can trace it as far back as the Ring of Gyges in Plato’s Republic (which was undoubtedly the model for Tolkien’s One Ring). Plato used the magic ring as a metaphor to explore the question of whether an intelligent person would remain moral if he did not have to fear capture and punishment.

Wells’ answer was a firm “no.” In the novella, originally serialized in Pearson's Weekly in 1897, Wells’ optical scientist Griffin decides to use his power of invisibility to become a national terrorist. Felled by an angry mob, the dying Griffin slowly turns visible again.

“By demonstrating the corrupting effects of the power of invisibility, The Invisible Man is a retelling of Plato’s myth of the ring of Gyges,” wrote Philip Ball in The Dangerous Allure of the Unseen. “It isn’t clear if this was Welles’ explicit aim, but that seems likely. He was deeply impressed by The Republic when it read it in his youth, not least for the alternative it offered to the stifling orthodoxy of Victorian society.”

In 1977, writer Doug Moench and artists Dino Castrillo and Rudy Messina adapted the story for Marvel Classics Comics. My late friend Roger Slifer was editor.

For an entertaining parlor game, ask your friends which super power they would prefer: invisibility or personal flight? The results will be telling, and generally spark an interesting discussion about expediency, ethics and life goals.

In the This American Life radio program, writer John Hodgman asked people that question. “He finds that how you answer tells a lot about what kind of person you are,” host Ira Glass noted. “And also, no matter which power people choose, they never use it to fight crime.”

Thursday, December 13, 2012

October 1976: “The Following Information Is Classified…”

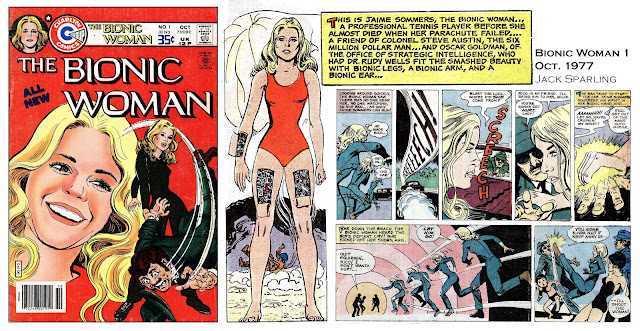

Martin Caidin’s 1972 novel Cyborg inspired the 1973-78 TV series The Six Million Dollar Man, which in turn spawned the TV show The Bionic Woman.

Airing from 1976 to 1978 and starring the bright and talented Lindsay Wagner, the science fiction superhero series was popular enough to produce a Kenner doll (with its own Bionic Beauty Salon playset) a record, a metal lunchbox, two paperback novels, a Parker board game and a five-issue comic book series from Charlton (1976-77).

Unlike its abortive 2007 remake, the original series managed to be optimistic and humanistic (without being saccharine).

Watching the last episode, I was surprised to find that, unlike most American TV programs, the show did not simply break off, or run out of gas and splutter to a stop. It effectively concluded, and concluded well.

The dispirited Jaime Sommers, tired and somewhat sickened after three years of being a superspy “robot lady,” quits the secret Office of Scientific Intelligence, only to find that she can’t quit — she’s government property. They intend to jail her.

The Bionic Woman meets The Prisoner.

This cynical, realistic take on what the U.S. government would do is a little surprising in a 1970s adventure show. She has an ally in her dash for freedom from American law enforcement — her ex-boss Oscar Goldman (Richard Anderson, who takes a break from exposition to enjoy a strong acting turn).

Jamie tells him, “I thought I was more than a pawn to you, or one of your little tools…”

“You’re hurting my arm,” Goldman replies.

Ever the compassionate heroine, Jamie takes time to help the alienated son of a blind man, and finds the solution to her own personal dilemma.

Wagner had specifically asked for a concluding episode, and the writer, Steven E. De Souza, worked all Wagner’s frustrations with doing a network series into Jamie’s emotions about her spy job.

The script, and Wagner’s Emmy-winning charm and acting ability, let the series finish with class.

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

September 1976: The Short Flight of the Human Rocket

What do you get when you cross Spider-Man with Green Lantern? Nova, the Human Rocket.

Introduced by writer Marv Wolfman and artist John Buscema in Nova 1 (Sept. 1976), the character was an attempt to recapture the teenage superhero lightning of Spider-Man in a bottle 14 years later.

But instead of a bitterly alienated science nerd, Richard Rider was an ordinary high schooler, good-hearted but not overly bright. As with the Silver Age Green Lantern, his super powers are transferred from an endangered and dying alien champion.

But the dying Green Lantern of Space Sector 2814, Abin Sur, had time to find the bravest man on Earth, Hal Jordan, and to use his power ring to check that he was also honest. The mortally wounded Centurion Nova-Prime Rhomann Dey just picked a kid at random.

And that angle gave the feature something of a Greatest American Hero vibe, with Rider learning to use his super powers on the job. And those were the satisfying if typical Standard Operating Procedure powers for a superhero — flight, super-speed, durability and super-strength.

His first run lasted only an unimpressive 25 issues. But I always thought Nova had potential, and at least his exit was as stylish as his entrance — for the final issue, his cover tag line was altered from “He’s here! The Human Rocket!” to “He’s gone! The Human Rocket!”

Friday, November 30, 2012

March 1976: The Sadness of Superman

A caped figure in red and blue leaping about the city skyline, Omega the Unknown seemed to be a visual wink at the early Superman and/or Captain Marvel.

But there ended the resemblance, because Omega was not to be a wish fulfillment figure. After all, in the 1976 series co-created by Steve Gerber, Mary Skrenes and Jim Mooney, he ended up being mistakenly shot dead by Las Vegas police.

“The 10-issue series follows the adventures of (two) protagonists, who interestingly don’t directly interact often but face thematically interlinked challenges,” noted comics historian Matthew Grossman.

James-Michael Starling’s world “…is a cockroach-infested, often cruel place and his repeated struggles with the uglier sides of high school suggest that to an emotional innocent, schoolyard bullying can be as harrowing as any battle with super-villainy.

“The laconic, initially silent Omega struggles with the role of superhero he finds himself unwittingly cast in. It’s a task he barely understands and finds himself pretty lousy at, losing many battles and surviving most of the rest through sheer luck. And much to the consternation of a superhero-wise public, he’s willing to let villains walk away when they offer valid reasons for looting the public.

“Both characters seem to be representations of adolescence struggling in an adult world.”

Though commercially unsuccessful, Omega was arguably ahead of its time, anticipating the ambience of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ 1986 Watchmen.

“Gerber was Marvel Comics’ auteur of absurdity,” Grossman observed. “Superhero comics, with their repetitive plots and nonsensical underpinnings, lend themselves to the absurdist preoccupation with meaninglessness, and the disillusionment of the period, reflected in Bronze Age comics’ move away from optimistic themes, provided fertile ground for explorations of psychological malaise.”

Charles W. Fouquette said, “It seems like a nihilistic version of Superman in a post-Watergate/Viet Nam 1970s world. … Gerber always did push the boundaries on conventional comics and we have to give credit to Marvel for giving him leeway for some of his ideas.”

Tuesday, October 23, 2012

June 1975: In a Mirror Darkly

Battling bodies careering into and right through arcane architecture — this superhero feature was clearly something different.

“One of the aspects of early Dr. Strange that Marvel Studios’ eponymous movie got right were the eerie clashes between Strange and various astral plane assassins,” observed comics historian Mark Engblom. “I felt like I was watching a (Steve) Ditko story come to life!”

In his first recorded exploit, Dr. Stephen Strange fought one of those conceptual, extradimensional entities who’d secretly harry our plane of existence throughout his career.

In his second adventure (Strange Tales 111, Aug. 1963, reprinted in Marvel Treasury Edition 6, June 1975), the Master of the Mystic Arts battled one of the mirror-image foes so common to superheroes — in this case, a treacherous, power-hungry sorcerer of equal ability who’d also been trained by the Ancient One. While Strange is pledged to use his power to protect people, his enemy intends to enslave them.

The villain introduced here had a name that fairly rumbled from the lips, “Baron Mordo” (with its suggestions of “morbid,” “morose” and “mordant”). JRR Tolkien also recognized the ominousness of the sound (“Mordor”), and so did Jim Shooter (“Mordru”).

Comics historian Jeff Rovin wrote, “Among the countless dark powers (Baron Mordo) has at his command are astral projection … altering his physical appearance; mesmerizing others while he’s in corporeal or spiritual form; summoning up a paralytic vapor and creating another vapor which can remove an entire apartment building from this realm and drop it into limbo.

From his European castle, Mordo projects his astral form to Tibet, where he telepathically commands the Ancient One’s servant to poison his meal. Sensing the danger in his Greenwich Village sanctum, Dr. Strange sends his own spirit soaring to the scene, where he engages Mordo in battle while arguing their philosophical differences. Strange defeats Mordo with shrewdness.

“I really liked the balance between the surrealistic mystic environs and the noir-ish street scenes,” recalled comics historian Vincent Mariani.

Friday, October 19, 2012

February 1975: Who Knows How to Break In to Comics?

INT. 909 THIRD AVE., NEW YORK — Day

New editor Denny O’Neil is shouting inside his DC Comics office.

A 1974 summer hire staffer runs in to check on O’Neil. He finds the writer-editor upset because DC had canceled and then un-canceled the Shadow title, leaving him with a comic book to publish immediately — but no script.

The young staffer realizes this is his chance to fulfill a lifelong dream of writing comics. Bluffing, he tells O’Neil he has a great idea for a story

What is it, O’Neil asks.

The staffer thinks fast. He and his wife had recently honeymooned at Niagara Falls, which daredevils once crossed on tightropes in the 1930s, the Shadow’s era. Could he use that?

“Uh … Picture a fight between the Shadow and a villain on that tightrope over Niagara Falls … at night … the roving searchlights catching a glimpse of him up in that sky!” the staffer improvised.

Good cover there, says O’Neil. Go on. Why are they fighting?

Still thinking on his feet, desperately, the staffer comes up with the idea of smugglers between the U.S. and Canada.

Smuggling what?

Drugs!

How?

In those barrels that people used to use to go over the falls!

O’Neil asks if he could have the script on his desk by 6 p.m. the next day, and the staffer says sure.

The Night of the Falling Death was published in The Shadow 9 (Feb.-March 1975), with interior art by Frank Robbins and a cover by Joe Kubert.

And the young summer hire who wrote it? He was Michael Uslan, who would go on to originate and serve as executive producer on the Batman movie franchise.

The anecdote appears in his memoir, The Boy Who Loved Batman.